8.1. OECD long-term economic model¶

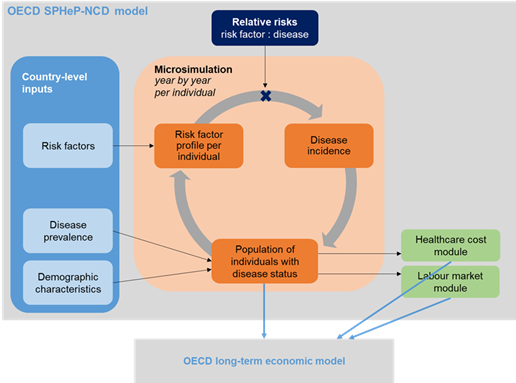

The impact of any risk factor to population health (e.g. obesity, alcohol consumption, etc.) or any disease (e.g. diabetes, cancer, etc.) on the larger economy is evaluated using the OECD long-term economic model. The OECD long-term economic model uses the short-run projections of the twice-yearly OECD Economic Outlook (EO). The EO includes historical estimates and short-run projections of potential output for each country based on a Cobb-Douglas production function with trend input components, namely trends in labour efficiency, employment and the productive capital stock. See below for further details.

8.1.1. ECO long-term economic forecast description¶

Note: The below long term scenario description is, with some adaptations, directly taken from [Guillemette and Turner, 2017 [27]].

The OECD long-term economic model projects GDP, GDPpc, employment rate, public health spending, primary revenue as share of GDP, the population and working-age population from 2020 to 2060. As a starting point, the OECD long-term economic model uses the short-run projections of the twice-yearly OECD Economic Outlook (EO). The EO includes historical estimates and short-run projections of potential output for each country based on a Cobb-Douglas production function with trend input components, namely trend labour efficiency, trend employment and the productive capital stock. This same production function sits at the core of the long-term model. Projections of trend labour efficiency are obtained by applying an estimated conditional convergence equation, which determines a country-specific long-run equilibrium based on a number of institutional and policy indicators [Guillemette, Kopoin, Turner and Mauro, 2017 [26]]. Projections of trend employment are done with a cohort-based model and use demographic projections from the European Commission and the United Nations [Cavalleri and Guillemette, 2017 [7]]. Capital stock projections are based on a partially estimated equation that typically keeps the growth contribution of the capital stock relatively small in the baseline scenario but allows policy shocks in alternative simulations, including shocks to government investment [Guillemette, Kopoin, Turner and Mauro, 2017 [26]]. […] Actual real GDP projections assume that any initial output gap closes gradually in the first few years of the projections; a Phillips-type equation determines the GDP deflator; and there are equations to project exchanges rates, interest rates, current accounts and a mechanism to ensure equilibrium between saving and investment at the global level. The ratios of health, long-term care and pension expenditure to GDP are taken from pre-existing work and are incorporated exogenously. Other primary expenditure is kept constant in real per capita terms, thus its ratio to GDP depends on the evolution of the trend employment to population ratio. [Guillemette and Turner, 2017 [27]].

8.1.2. Impact on fiscal outcomes¶

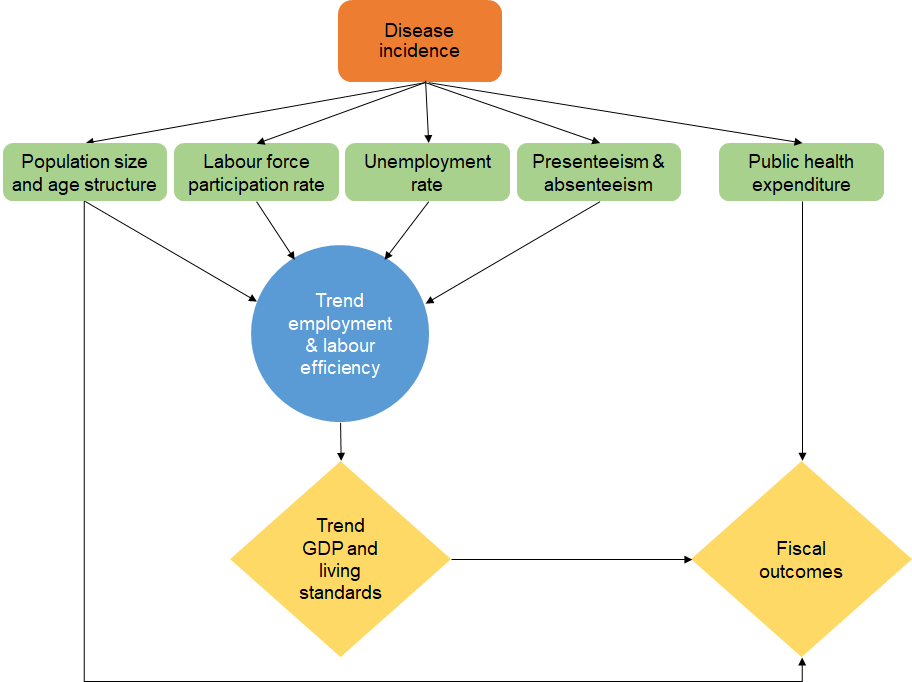

Gross Domestic Product (GDP), GDPpc and other fiscal outcomes of the ECO model are affected by: a) population size and age structure; b) labour force participation; c) unemployment; d) presenteeism; e) educational attainment; f) public health expenditure using employment trends (a-e); and f) labour trend efficiency (disease burden and (e)), as well as fiscal outcomes ((a), (f)).

The ECO model uses the following outputs from the SPHeP-NCD Model:

Difference in employment rates (including both employment as well as absenteeism and presenteeism converted to full-time employment equivalents).

Difference in life expectancy.

Difference in healthcare expenditures.

Fig. 8.1 Linking the OECD SPHeP-NCD model to OECD-ECO’s long-term GDP forecast¶

The OECD SPHeP-NCD model models the employment rate; productivity; population dependency ratio (i.e. ratio of dependents (people younger than 15 or older than 64) to the working-age population); changes in life expectancy; and healthcare cost for the business-as-usual scenario and intervention scenario. These outputs are then used as inputs for the OECD-ECO model, which shows the impact on the GDP and fiscal pressure (see Fig. 8.2).

The medium term GDP forecasts in the OECD long-term economic model are a function of productivity, size of the working age population, education, and labour force participation. By varying these inputs (while keeping education constant) under different scenarios, the output gap (difference of GDP) is modelled at the macro-economic scale. Fiscal pressure is measured as government primary revenue needed to stabilise the public debt ratio as percentage of GDP. This is equivalent to an overall tax rate.

The long-term economic model is run with and without an adjustment for retirement age.

Fig. 8.2 Link between OECD SPHeP-NCD and OECD long-term economic models¶